Science and philosophy were long regarded as the result of the ‘Greek miracle,’ a unique achievement incomparable with the contributions of earlier civilizations, particularly those of Mesopotamia and Egypt. This view, while not entirely abandoned today, is now considered overly radical. Whatever its merits, it is undeniable that Greece was influenced by these earlier civilizations; yet it processed their contributions in a distinctly original manner that ensured the enduring relevance of its thought.

Egypt, Mesopotamia, the Near East, and the regions that would become Greece had been in contact since deep antiquity. In the Neolithic period, the Aegean Sea already served as a corridor for traffic between Asia Minor, the islands, and mainland Greece. Around 3000 BCE, metallurgical techniques from the Near East were introduced into Greece. In Theban tombs dating from the reign of Thutmose III (circa 1500 BCE), there are depictions of offering-bearers referred to as Keftiu, generally thought to be Cretans. Egyptian documents from Tell el-Amarna attest to contacts with the peoples of the Near East and Mesopotamia. In the fourteenth and thirteenth centuries BCE, the Hittite archives mention a kingdom of achchiyawa, which some scholars identify with the Achaeans (Greeks). Cretan and Mycenaean artifacts, including ceramics, have been found in Syria and Egypt.

Such interactions also occurred in later periods, whether directly or mediated by Phoenician sailors and merchants. Cyprus and Ugarit (modern Ras Shamra) appear to have been significant hubs of exchange due to both their geographical position and historical circumstances. Cyprus, initially within the Cretan-Mycenaean sphere, hosted Phoenician trading posts by the 10th century BCE and subsequently came under the successive control of the Assyrians (at the end of the 8th century), the Egyptians, and finally the Persians. Consequently, the island exhibits a blend of influences from all these civilizations.

In the period most relevant here – the 6th and 5th centuries BCE – interactions intensified due to the westward expansion of the Mesopotamian empires, beginning with their successive conquests of Egypt and culminating in the Persian Wars. Egypt was first conquered by the Assyrians (Thebes fell to Ashurbanipal in 663 BCE). It briefly regained independence following the disintegration of the Assyrian Empire but fell to the Persians in 525 BCE, remaining under their control until 405. These events inevitably fostered reciprocal influences.

Even before Cambyses conquered Egypt, his father Cyrus – the founder of the Persian Empire in 539 BCE – had extended his rule to Asia Minor and to the Lydian kingdom of Croesus. The Greek cities of the Ionian coast were thus brought under Persian control, with local tyrants installed in the service of the empire. In 499 BCE, these cities revolted with Athenian support, igniting the Persian Wars. Miletus was destroyed in 494. Darius attempted to extend Persian rule into mainland Greece but was defeated at Marathon in 490. His successor Xerxes resumed the offensive but was also defeated, in 479, leading to the liberation of the Ionian cities. During this period of subjugation and subsequent conflict, ideas developed in the various Mesopotamian empires were able to permeate Greek civilization, which was itself undergoing significant transformation.

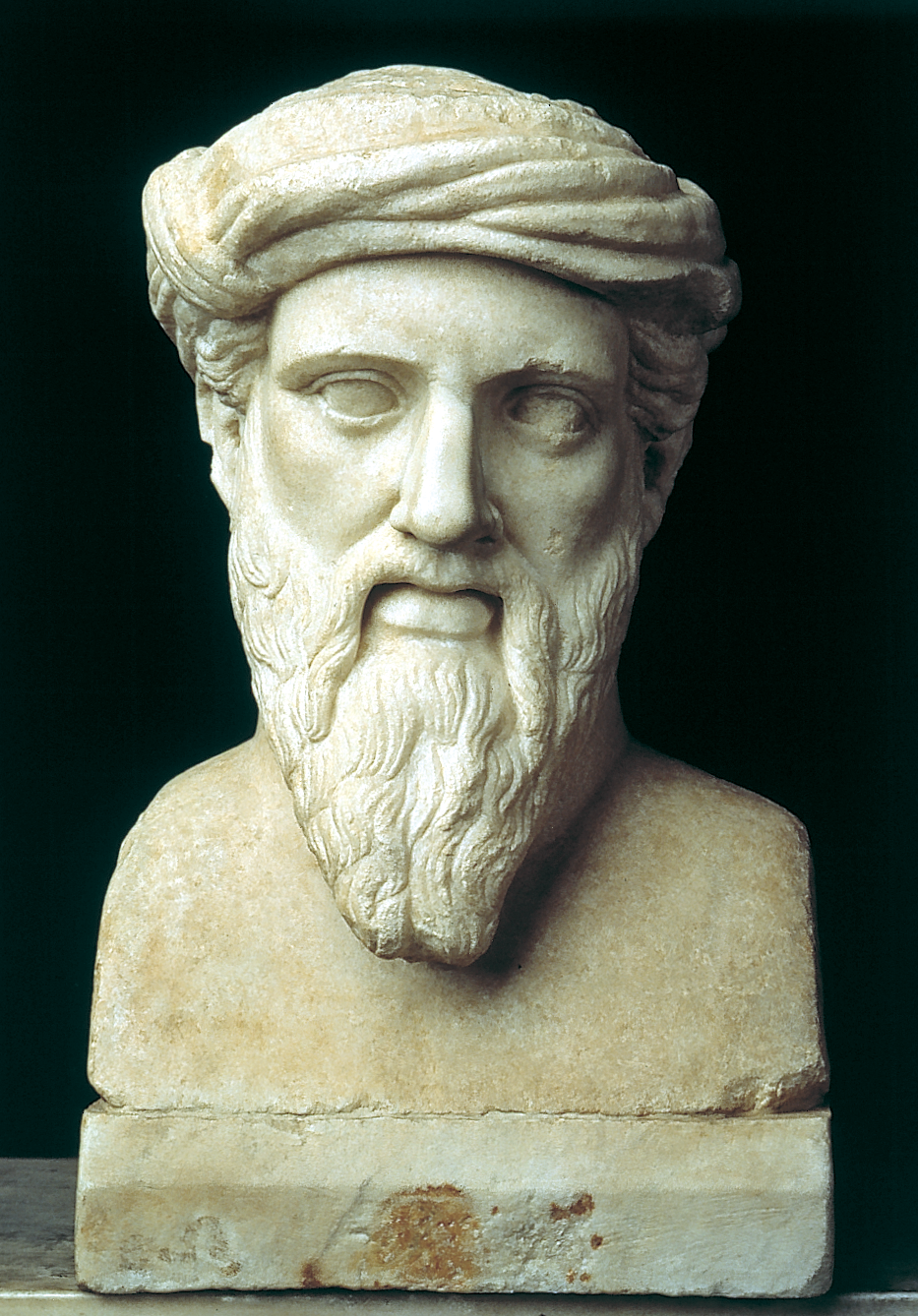

At the same time, Greek civilization – represented in Miletus by Thales, Anaximander, and Anaximenes; in Ephesus by Heraclitus; in Samos by Pythagoras – was shifting from the Ionian coast to the Greek mainland. More broadly, there was a general mixing of peoples and a westward movement of civilization (Rome, mythically founded in 753 BCE, began to take shape at the end of the 7th century). In the 6th century BCE, Greece became a center of maritime trade between the Eastern empires and the West, which was itself beginning to develop (Italy, Gaul, Spain).

Later, in the second half of the 4th century BCE, the conquests of Alexander (356–323 BCE) would further intensify contact between the Greek world and both the East and Egypt. These campaigns led to the Hellenization of those regions, but also to increased Eastern and Egyptian influence on Greece. By this time, however, Greek civilization was already firmly established, and its foundations securely laid, so these later influences were less decisive.

The period in which Greek philosophy and science emerged was thus one of great upheaval, marked by intense and often conflictual contact between Greece, Egypt, and the broader Near East. Yet cultural exchange alone does not suffice to produce deep influence; despite these longstanding interactions, there was neither a standardization of civilizations nor a major intermingling of ideas – at least not before the Hellenistic period.

Mesopotamian and Egyptian civilizations each maintained their distinct identities. Both were monuments to stability and, especially in the case of Egypt, inclined toward inwardness and self-preservation. As for Greece, aside from the Cretan-Mycenaean period – which, for a few centuries, attained a level of civilization comparable to that of Mesopotamia and Egypt, albeit on a much smaller scale – its overall level of development remained modest. It was therefore not yet in a position to fully assimilate all that its exchanges might have offered. Thus, although Egypt and Mesopotamia undoubtedly exerted influence on Greece, there were no massive borrowings, nor direct incorporation of unaltered elements – at least not during the period in question, the 6th and 5th centuries BCE.

On these questions, there is also the testimony of the Greeks themselves, who often acknowledged their debt to Eastern and Egyptian civilizations for certain forms of knowledge. Herodotus, for example, attributes the invention of geometry to the Egyptians, who, he claims, developed it out of necessity to remeasure the boundaries of their fields after the annual inundation of the Nile (Histories II.109). He credits the Babylonians with the invention of the gnomon, the sundial, and the division of the day into twelve parts (ibid.). Porphyry reports that Pythagoras learned geometry from the Egyptians, arithmetic from the Phoenicians, and astronomy from the Chaldeans (Life of Pythagoras, 6). Hippolytus describes Pythagoras traveling to the East, where he meets Zoroaster (Philosophoumena I.II.12), while Isocrates asserts that he acquired his knowledge in Egypt (Busiris, 28). Proclus claims that Thales brought geometry back from Egypt (In primum Euclidis elementorum librum commentarii), and Diogenes Laërtius recounts that he calculated the height of the pyramids by measuring their shadows (Vitae philosophorum I.27). There is also a tradition that Hippocrates of Cos studied medicine in Memphis, Egypt. More generally, legend has it that Cadmus, the son of a Phoenician king and brother of Europa, invented and introduced writing into Greece – a plausible narrative, given that the Greek alphabet derives from the Phoenician consonantal script.

Thus, within Greek tradition itself, one finds numerous references to borrowings from Egypt, Babylonia, and the Near East. Whatever the historical accuracy of individual claims, they collectively attest to a memory of sustained contact and cultural exchange between these civilizations. At the same time, this acknowledgment of influence did not preclude the emergence of a critical attitude. Plato, for example, characterizes the Greeks as distinguished by their love of knowledge, whereas, in his view, the Phoenicians and Egyptians excelled primarily in their love of wealth (Republic IV, 435e). This reflects an awareness of a qualitative distinction between Greek knowledge – conceived as ‘pure’ or contemplative – and the more practical or application-oriented knowledge of Egypt and the Orient. However, such conclusions should not be drawn too hastily. One must resist the temptation to deny the Egyptians, Phoenicians, and Babylonians any form of disinterested inquiry or intellectual curiosity, even if such inquiry did not take the form of a systematic philosophy akin to Plato’s.

In addition to historical data and Greek testimonies, we also have documents pertaining to the ‘sciences’ developed by these ancient civilizations. Although one should not overlook the various artifacts – architectural remains, artistic objects, tools, and so on – that shed light on the technical practices of the time, it is primarily through written documents that we can speak meaningfully about the sciences. However, such documents are both fragmentary and variable in nature across different civilizations.

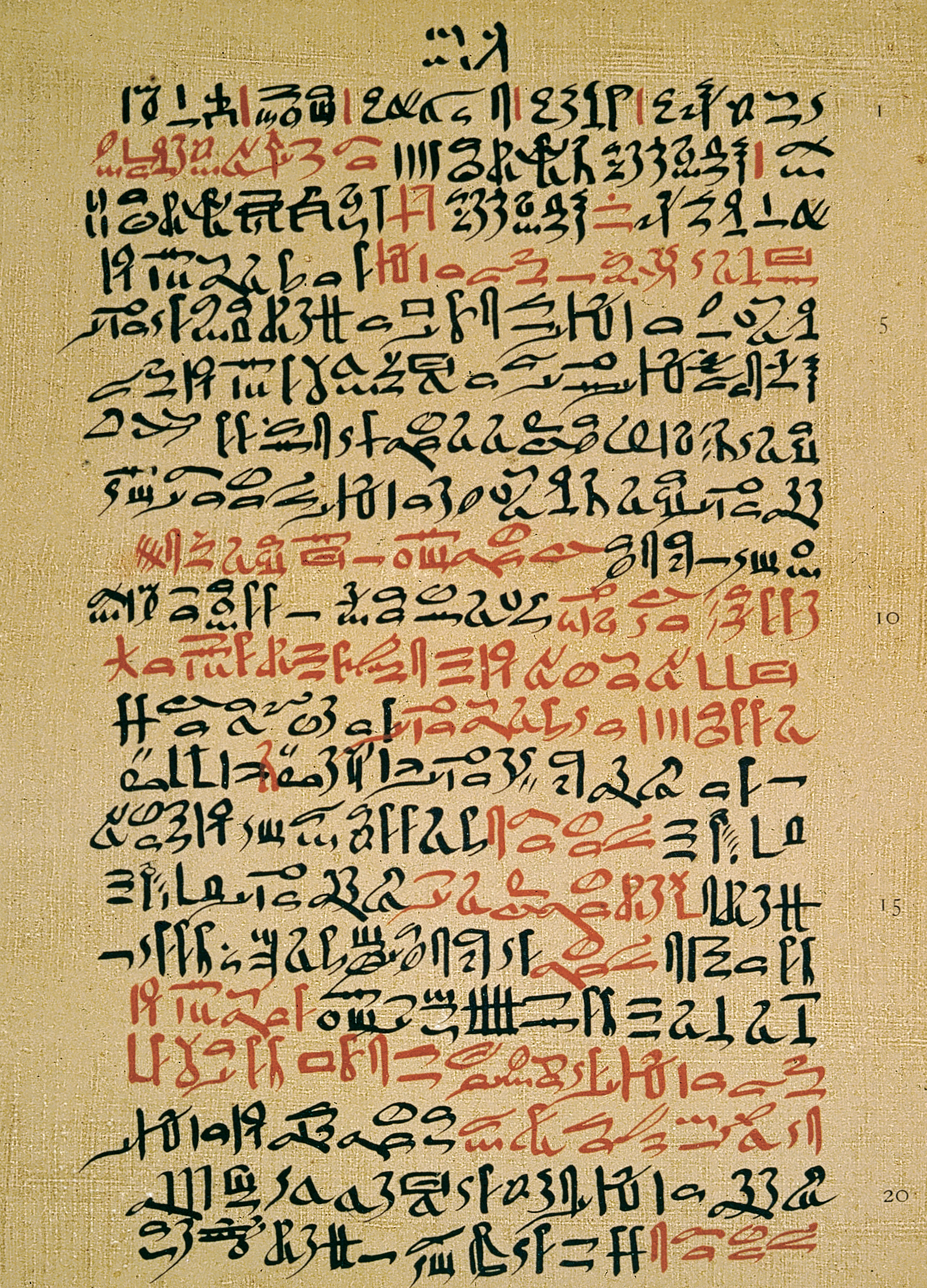

First, there is a fundamental difference in the type of writing used. Mesopotamian documents are written in cuneiform script, Egyptian ones in hieroglyphic script (or in its cursive variants, hieratic and demotic, depending on the period and the type of document), while the Greeks employed an alphabetic system. Even though both Mesopotamian and Egyptian scripts evolved to include more phonetic elements, they remained largely ideographic and never attained the full phonetic character of the Greek alphabet. The Phoenician script, from which the Greek alphabet ultimately derives, was phonetic but recorded only consonants, as is common in many Semitic languages.

The nature of the writing system influences the nature of what can be expressed. Ideographic writing is ill-suited to conveying grammatical structures and complex, abstract notions. Such scripts are more apt to document ‘positive,’ factual knowledge than to capture the conceptual spirit in which that knowledge was formulated. In contrast, alphabetic writing, with its greater phonetic precision, is better equipped to convey subtle nuances of thought. Since oral teaching has largely been lost, we are less informed about the intellectual orientation of the Mesopotamians and Egyptians than we are about that of the Greeks. As a result, the scientific knowledge of the former may appear overly pragmatic or ‘down to earth,’ due in part to the limitations of ideographic expression, whereas the more philosophical character of Greek science is accentuated by the expressive flexibility of the alphabet.

Beyond the differences in writing systems, there are also differences in the physical nature of the documents themselves. The durability of materials and the favorable climate have preserved many Mesopotamian texts (on clay tablets) and Egyptian texts (on papyrus). By contrast, Greek documents from the same period are extremely rare. What we have are mainly traditions reported by authors – often writing at a later time – whose works have reached us through successive manuscript copies, either in the original language or in translation, both of which are susceptible to alteration and distortion.

This mode of transmission also entailed a selective process. While Mesopotamian and Egyptian texts include what appear to be simple ‘school exercises’ as well as more scholarly works, we possess no equivalent school materials from ancient Greece. Such elementary texts were unlikely to be copied and recopied over the centuries, and thus have not survived. What remains are only works deemed important enough to preserve. Just as the diversity of writing systems has shaped our perception of ancient science, so too has this selective transmission contributed to a skewed understanding of the intellectual landscape these texts reflect.

Beyond the differences in documentation, Mesopotamian, Egyptian, and Greek sciences each exhibit distinctive characteristics, with the former two clearly differing from the latter. Egyptian and Mesopotamian sciences were more concerned with procedures and results – however approximate – than with the pursuit of pure knowledge or formal demonstrations. Judging from the fragmentary state of the available evidence, their levels of development appear comparable, though not identical.

In both Mesopotamia and Egypt, geometry involved the calculation of areas and volumes – exact in the simplest cases, approximate in the more complex – and it sometimes approached concepts resembling our Pythagorean and Thales’ theorems. For both civilizations, geometry was primarily an applied science, seldom concerned with proof, although Egyptian approximations appear somewhat more refined than those found in Mesopotamian sources. For instance, the Rhind Papyrus (circa 1650 BCE) includes a calculation of the circumference of a circle that corresponds in modern terms to π ≈ 3.1604, whereas Mesopotamian methods typically yield \(\pi \approx 3\). Similarly, the Moscow Papyrus (circa 1800 BCE) offers the exact formula for the volume of the frustum of a square pyramid, while the Babylonian tablet YBC 5037, dating from roughly the same period, provides a result for the same problem by approximating the frustum as the superposition of two rectangular parallelepipeds – that is, using the formula \(V = h/2(a^2 + b^2)\) instead of \(V = h/3(a^2 + ab + b^2)\), where \(V\) is volume, \(h\) is height, \(a\) is the side of the base, and \(b\) is the side of the top.

Arithmetic, by contrast, seems to have been the particular domain of Mesopotamian expertise. The Egyptians were relatively poor calculators; multiplication and division posed difficulties, and they were forced into complex maneuvers due to their cumbersome system of fractions. Mesopotamian scribes, on the other hand, manipulated numbers with facility, solved quadratic equations (as in tablet BM 13901), and even employed what we would today recognize as logarithmic techniques (e.g., in tablet VAT 8528). This facility with numbers was also tied to a form of numerical mysticism, which was largely absent from Egyptian tradition – at least until the Hellenistic period.

Astronomy, too, was highly developed in Mesopotamia, where it was even mathematized, although it remained closely linked to astrology. In Egypt – where textual evidence on the subject is more limited – astronomy appears to have been less mystical but also less advanced, and it did not undergo a similar process of mathematization. It seems, then, that for Mesopotamians, mysticism – almost to the point of superstition – was a driving force behind their engagement with both celestial and numerical phenomena.

Conversely, in medicine, this mystical character of Mesopotamian culture may have been a hindrance. Egyptian medicine, particularly its surgical practice, appears – at least in the limited extant texts – not necessarily more scientific, but at least less entangled with magical thinking. One can even discern the beginnings of a physiological explanation of disease. In both traditions, medicine and surgery remained empirical, but Egyptian practice was less encumbered by incantations and magical rituals than its Mesopotamian counterpart.

In general, whether in mathematics, astronomy, or medicine, Egyptian science seems more pragmatic and application-oriented, whereas Mesopotamian science was more deeply rooted in mysticism. This difference may stem from the varying relationships between religion and political power: in Egypt, religion was more closely tied to state authority, while in Mesopotamia – especially under Persian rule – each people retained its own religion, with political unity remaining largely administrative. In this way, Egyptian religious sentiment may have been channeled and stabilized by political structures, whereas in Mesopotamia it remained freer and more diffusely expressed.

In both cases, however, we are still far removed from what would become Greek science. Mathematics in Mesopotamia and Egypt consisted largely of lists of procedures to be followed case by case, along with calculation tables to assist in their application. Although these civilizations achieved many forms of ‘positive’ knowledge – such as the volume of a truncated pyramid or the resolution of quadratic equations – these accomplishments were fundamentally different from those of Greek mathematics. The same applies to the natural sciences: while here the issue is less one of formal proof than of understanding physical, astronomical, or biological phenomena, Greek science sought to explain such phenomena in rational terms, free from myth and magic. Where Greece pursued intelligibility, Egypt and Mesopotamia prioritized practical effectiveness – an empiricism often accompanied by magical or mystical interpretations.

What influence did Mesopotamian and Egyptian sciences have on Greek science – prior to the Hellenistic period, when Alexander’s conquests led to a certain mingling of civilizations? First and foremost, there is something so self-evident that it is often overlooked: the very existence of disciplines already defined in relation to their specific objects. Long before the Greeks, there were distinct areas of study – one concerned with numbers and calculation (what would later be termed ‘arithmetic’), another with lengths, surfaces, and volumes (‘geometry’), a third with celestial phenomena (including stars and meteorological events, often conflated under ‘astronomy’), and a fourth with disease (medicine, whether or not linked to a physiological understanding of health). The documents of these civilizations, by grouping knowledge and problems according to subject matter, attest to a structuring of knowledge according to its object.

Such division into disciplines may seem natural – and indeed, it is found in other cultures unrelated to the ones discussed here (such as China). But in this particular context, where there was contact between civilizations at different levels of development, it is reasonable to suppose that the less advanced civilization (Greece) may have borrowed from the more developed ones. Rather than independent reinvention, importation – possibly followed by adaptation – is a plausible scenario.

Similarly, Greece may have adopted, with modifications, the rudiments of various scientific disciplines, just as it borrowed its writing system from the Phoenicians, adapting it to fit the Greek language (e.g., by introducing vowels). For example: the use of base-10 numeration in Crete and Greece, as in Egypt (with 10 also functioning as a secondary base within the Babylonian sexagesimal system, whose influence persists in our measurements of angles and time); the basic operations of arithmetic – addition, subtraction, multiplication, division – as well as slightly more advanced ones, such as powers and roots; calculations of elementary areas and volumes; and likely some preliminary astronomical notions (zodiac, ecliptic, planets). These are all elements that the Greeks could theoretically have discovered independently, but which, given their prior existence in neighboring civilizations with which Greece was in contact, may well have been borrowed and adapted. While we cannot affirm this definitively, the elementary and ‘culturally neutral’ character of this knowledge made such transfer feasible – unlike more complex aspects of Egyptian and Mesopotamian sciences, which would have been more difficult for an intellectually nascent Greece to absorb, particularly if they were marked by the unique traits of their respective cultures.

These remarks also apply to more refined concepts which, when present in the societies with which the Greeks had contact, could have been incorporated into Greek science – not immediately, but gradually, as Greek science evolved and became capable of assimilating them by recasting them in its own terms. To the extent that Mesopotamian and Egyptian sources contain elements comparable to what we now refer to as the theorems of Thales and Pythagoras, it is plausible that such ideas were transmitted to Greece – perhaps even through Thales and Pythagoras themselves – although it was only later that the Greeks reformulated them explicitly as theorems. The tradition reported by Diogenes Laërtius, according to which Thales measured the height of the pyramids by comparing their shadow to that of a stick (implicitly applying the theorem of similar triangles), likely preserves a memory of the Egyptian origin of this knowledge.

Similar observations apply to astronomy. Doxographical sources attribute to Thales the prediction of a solar eclipse during the “war between the Medes and Lydians” (Clement of Alexandria, Stromata, I, 65, citing Eudemus’ History of Astronomy; see also Herodotus, Histories, I, 74). If Thales did indeed predict the eclipse, he could only have done so by drawing on the expertise of a Mesopotamian astrologer – perhaps one who accompanied the troops – likely without fully understanding the astronomical principles behind it. This does not exclude the possibility that such principles would later be understood and further developed in Greece.

In the case of medicine, some parallels – more or less direct – can also be noted. Take, for example, conceptions of the heart. According to the Ebers Papyrus (circa 1550 BCE), the body is traversed by a network of ‘channels’ through which various fluids circulate – possibly including life and death ‘breaths’ mentioned earlier in the text. The heart plays a central role, issuing commands to the organs via these vessels. In Aristotle’s physiology, the heart likewise occupies a central position as the seat of the soul and thus of life itself. A thesis – echoed in Hippocratic and Aristotelian treatises – maintains that air drawn in by the lungs is heated in the heart and then diffused throughout the body via the arteries. This warm breath, the pneuma, animates the body. Here, too, there is an evident analogy with the Egyptian notion of a ‘breath of life’ and the idea that the heart ‘speaks’ to the organs through a vascular system.

Early Greek science also includes ‘para-scientific’ notions that may have been imported – or that may reflect a much older common cultural substratum. For example, Thales’ water-based cosmology echoes the myth of Oceanus found in Homer (Iliad, XIV, 201, 246, and 302; see also Aristotle, Metaphysics, I, 3, 983b 30). But it also resembles a Sumerian view in which the Earth is enclosed between waters above and below, and the cosmology found – implicitly – in the Bible (Genesis 1:6-9). This likely reflects a shared ancient heritage, rather than a direct borrowing.

A similar case is found among the Pythagoreans, who believed that odd numbers were male and even numbers female. This idea anticipates the theory of the One and the Dyad that Aristotle attributes to the Platonists (probably Speusippus and Xenocrates) in Metaphysics (XIV, 1, 1087b), though many doxographers trace it to Pythagorean sources. In this theory, the One is the determining unity (odd and mixed), while the Dyad is the multiplicative force (even and feminine), and their interaction gives rise to the number system. In Sumerian numeration, the number 1 is called gesh, which also means ‘man’ or ‘millet,’ while the number 2 is min, which also means ‘woman’ or ‘female’ (Guitel 1975). There is a clear affinity between these conceptions – likely the result of a shared cultural background rather than direct borrowing. This same background can be seen in Egyptian arithmetic, where multiplication was performed by a sequence of successive doublings (followed by the addition of partial products), as if duplication – the Two, the Dyad – were the primary means of generating multiplicity.

This list of analogous or borrowed knowledge could be extended, but it would soon become tedious. In truth, it is nearly impossible to state with certainty what was borrowed and what was independently developed. It is more productive to reflect on the limitations of these borrowings – limitations rooted in the deeper, structural differences between the respective scientific outlooks. We will explore these limitations through examples drawn from mathematics, astronomy, and medicine.

Both the Babylonians and the Pythagoreans adhered to a form of numerical mysticism. Such mysticism is widespread throughout the world and takes various forms. The kind we are dealing with here clearly stems from the difficulty of defining the nature of numbers. For instance, if there are three apples on the table, the apples are indeed there – but the number three is not. Where is it? What is its ontological status? Numbers do not belong to the natural world, yet they seem to govern it, as evidenced by their application in ‘arithmetical laws’ – notably in Babylonian astronomy or Pythagorean music, as we shall see. Geometrical figures, no matter how abstract, retain a perceptible quality that gives elementary geometry the appearance of a natural science. Numbers lack this sensory and almost concrete dimension, which allows them to easily slip into the realms of the supernatural and mystical. Their domain, like that of the gods, lies ‘above’ nature, whose order they nonetheless govern. Thus, how this ‘world of numbers’ is conceived and structured, and how it relates to the sensory world, is of fundamental importance.

In Babylon, numbers were associated with gods, who were assigned higher or lower numerical values according to their rank in the pantheon. Anu, the principal god of Heaven, was associated with 60 – the base of the Babylonian numerical system; Enlil, his son and god of Earth, with 50; Sin, the Moon god, with 30; and so on. Lesser demons had to make do with fractional values (Bottéro 1952; Ifrah 1994).

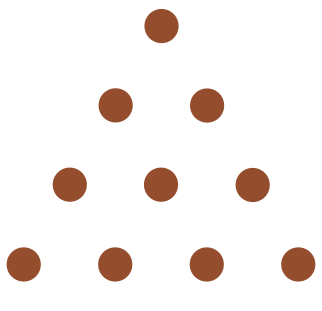

The Pythagoreans, in contrast, employed a more sophisticated system – though not necessarily more egalitarian, given the aristocratic nature of their sect. Rather than a straightforward ascending numerical order (typical of the Babylonian notion of progression, especially in astronomy), they assigned a ‘structural value’ to numbers, based either on their intrinsic characteristics or their relations with other numbers. However, this structural value was not always well-defined, nor was its mathematical significance always clear. For example, the Pythagoreans placed great importance on the number 10, the base of Greek numeration. While the Babylonians chose 60 as a base and associated it with their principal deity for practical reasons, the Pythagoreans justified the preeminence of 10 with arguments concerning its ‘structure.’ In a fragment attributed to Speusippus – Plato’s nephew and his successor at the Academy, reputed to be a Pythagorean – various such reasons are listed. Among them: 10 includes as many even as odd numbers, as many prime as composite numbers, and is the sum of 1, 2, 3, and 4 (fig. 2) – representing the point, the line, the plane, and the volume, respectively.

Some of these arguments may seem extravagant, but they reveal a conception of number value that goes beyond a simple hierarchical ranking. The Pythagoreans did not associate the number 10 with a supreme deity; rather, they explored the number’s internal structure to explain its special role in arithmetic – and, by extension, in geometry.

Other numbers also held special significance, often on more solid grounds. So-called ‘perfect,’ ‘abundant,’ or ‘deficient’ numbers are those equal to, less than, or greater than the sum of their divisors, respectively. Two numbers are ‘amicable’ when each equals the sum of the other’s divisors. Prime numbers, having no divisors other than themselves and 1, were also singled out. All of these designations reflect a structural or generative conception of numbers (i.e., as products of addition or multiplication starting from the unit). Moreover, numbers can relate to each other through various proportions – arithmetic, geometric, harmonic, musical – which were of particular importance to Pythagorean mathematics. These interrelations formed a complex web far richer than the Babylonians’ pantheon-based hierarchy.

This conceptual difference is also evident in mathematical applications. A Mesopotamian text, as noted, uses what we would today call a base-2 logarithm – an idea that might seem implausible but is fairly intuitive when approached through tables of calculation. Many Mesopotamian problems appear to have been inspired by such tables. Simply observing them could reveal numerous relationships between numbers that could be used to solve problems. Consider, for example, a table of powers of 2, such as tablet MLC 2078 from the First Babylonian Dynasty:

| 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 2 | 2 × 2 | 4 |

| 3 | 2 × 2 × 2 | 8 |

| 4 | 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 | 16 |

From this, one might notice the relationships among 2, 3, and 8, expressed today as \(2^3 = 8\), or \(\log_2{8} = 3\). Even without a full abstract grasp of powers or logarithms, such relationships are readily observable in the table and can be employed in practical computation and problem-solving.

The Pythagoreans also studied numbers and their relationships in another manner: through geometric figuration, where each unit is represented by a point, and these points are arranged into various geometric shapes (squares, rectangles, triangles, cubes, etc.). This method – possibly prompted by the limitations of Greek written numeration – helps reveal various arithmetical properties. For instance, the sequence of odd numbers can be visualized using gnomons (L-shaped additions to squares):

○ ○ ○ ○

○ ○ ○ ○

○ ○ ○ ○

This representation allows one to see – and to understand – that the sum of successive odd numbers results in a square number (e.g., \(1 + 3 + 5 = 9; 1 + 3 + 5 + 7 = 16\); etc.). This is a property intrinsic to the numbers themselves. While it may be used in calculation strategies, it is not confined to practical utility. This contrasts with the earlier example (of the Babylonian tables), where numbers were understood only in terms of their placement in a table, and properties were extracted solely for practical calculation.

Here, we find a fundamental difference in how numbers are conceived. In Babylonia, they were considered within the framework of calculation – that is, for practical effectiveness. This practical approach was reinforced by their association with gods, ranked according to a pantheon hierarchy, which lent a ‘supernatural’ character to numbers and perhaps justified their practical power.

In contrast, the Greeks viewed numbers in and of themselves – as an autonomous domain with intrinsic properties, independent of any utilitarian function or divine association. Geometric figuration served to make these properties intelligible. (After the discovery of irrational numbers, ‘number-points’ would be replaced by ‘number-segments’.) Still, beyond these representations, the ontological status of numbers remained elusive, giving rise to a form of numerical mysticism in Pythagorean thought – yet a mysticism that was more abstract and less entangled in practicality than that of the Babylonians.

A similar distinction applies to geometry. In Greece, the focus on the figures themselves led to the pursuit of rigorous demonstrations. By contrast, Egyptian and Mesopotamian geometry was geared toward practical applications and tolerated approximation. However, the philosophical question of the status of geometrical objects was less pressing than that of numbers. It appears that Mesopotamia and Egypt largely ignored it. In Greece, the issue would arise later – particularly after the discovery of irrational numbers – when philosophical inquiry transitioned from a numerical mysticism to a ‘geometrical god.’

In Babylonia, stars – like numbers – were considered divine; if not identified directly with gods, they were at least believed to harbor or represent them. Astronomy was primarily astrology, but it was also mathematized. Tablets from the Seleucid period attest to this (Neugebauer 1955). Although Mesopotamia was then ruled by a Greek dynasty, the methods used in these tablets are not Greek (despite their adoption in Hellenistic astrology; see Neugebauer 1990). These methods likely stem from an older local tradition, of which they represent the culmination.

This mathematical astronomy relies on calculations based on arithmetic progressions, without resorting to geometrical models of stellar motion. Such progressions are found in Babylonian mathematics outside of astronomy and well before the Seleucid period – for instance, in tablet STR 362 from the First Babylonian Dynasty. Similar progressions appear in Egyptian mathematics (problems 40, 64, and 79 of the Rhind Papyrus, circa 1650 BCE), but the Egyptians did not apply them to astronomy. The Babylonians, on the other hand, used them to calculate the positions of the ‘wandering’ stars (Sun, Moon, and planets), particularly during significant phenomena (appearances, disappearances, full moons, etc.).

These positions – whether observed or calculated – were expressed in what we would today call ‘angular coordinates,’ relative to the ecliptic and the zodiac. An observation provided the coordinates of a specific star at a given date; to determine its position at another time, one would apply arithmetic progressions to those coordinates. What concerns us here is not so much the details of these calculations, but the principle behind them: how the Babylonians came to use mathematics in astronomy, and why they chose arithmetic – especially progressions – over geometric models.

In Babylonia, both geometry and arithmetic were applied in agriculture and commerce – for example, in calculating the area of a field, the volume of beer, or pricing goods. These were applications, but ones that remained strictly within the mathematical domain: their outcomes could be exact, false, or approximate, yet always according to mathematical criteria. The domain remained mathematical, involving concepts like area, volume, and price – not physical notions.

Astronomy, however, presents a different case. Here, one does not merely calculate based on measured quantities (like coordinates instead of field dimensions); rather, one predicts a physical event – namely, the position of a celestial body on a future date. Measurement plays a role (comparable to that in agriculture or commerce), but the calculation anticipates the future, not a static mathematical quantity. Its value depends not only on mathematical coherence, but also on its correspondence to physical reality. The ultimate test of the method lies in whether the predicted future observation occurs. In this context, calculation becomes a tool for forecasting – a major concern in Babylon, judging by the quantity and diversity of divinatory practices documented (Contenau 1940).

That the Babylonians used arithmetic in astronomy – when geometry, with its quasi-concrete character, might have seemed more apt – is likely due to two reasons:

First, the computation of a star’s position may have been modeled after the formation of numbers. A star’s position (represented by numerical coordinates) leads to its subsequent position through a progression or a combination of progressions, just as a number generates another number in a sequence (the simplest being the arithmetic progression of ratio 1: i.e., \(1, 2, 3, 4,\cdots\).

Second, there is an almost intrinsic link between numbers and time. In enumeration, numbers proceed in temporal succession, in an increasing quantitative order. This is an arithmetic progression of ratio 1 unfolding through time – a generation of numbers that is temporal. Here, time is not conceived as a spatial dimension (as in geometry), but as the time of speech, a counted time, a rhythm. Therefore, arithmetic – especially progressions – is suited for anticipating future elements. This is especially true in astronomy, since stars have always served to measure and mark time (days, months, seasons, years). In Babylonia, where stars were associated with gods, and gods themselves linked to numerical mysticism, the scansion of time by stars and the scansion of time by numbers converge.

Astronomical calculation in Babylon functioned as a sort of algorithm, likely derived from tables of observations recording stellar positions over extended periods. For us, the geometric model of celestial motion renders the calculation of star positions intelligible and transparent. In Babylon, the absence of such geometric modeling made the ‘astronomical algorithm’ resemble a formula of divination – an arithmetic formula that yielded results confirmed by observation, but whose validity rested solely on that observation.

This had two important consequences, revealing the limits of an empirical form of ‘science.’ First, calculation was content with approximation: the goal was to predict the star’s position, not to explain its motion. The more precise the formula, the better – regardless of whether its complexity made it unintelligible. Second, in the absence of a geometric model that could provide intelligibility, the approximate match between the calculated and observed position likely reinforced a mystical worldview in which numbers, stars, and gods were bound by enigmatic relationships. The astronomer was thus a kind of magician, using formulas he had to extract from exploration of both the divine realm of the stars (aided by various observational instruments) and the mystical realm of numbers – hence the seemingly gratuitous numerical juggling in Babylonian tradition.

In contrast, Greek astronomy developed as an essentially geometric endeavor. This shift had profound consequences, notably visible in Plato and Eudoxus, but already present among the Pythagoreans. Greek astronomy sought to reduce the stars’ apparent (and in the case of the planets, highly erratic) motions to regular circular movements or combinations thereof. This circular regularity eliminated from celestial motion any inherent capacity for transformation: it reduced movement to a repetition of the same. The star was regularly returned to its prior position, and its orbit became the set of these periodic positions rather than the actual trajectory of a moving body.

This amounts to a denial – not of motion per se – but of any change resulting from it. It constitutes, rather, an affirmation of permanence and eternity: circular motion, regarded as the quintessential eternal motion, is paradoxically a kind of motion that leads nowhere. This geometrization thus removed the stars from the realm of change, bestowing upon them – if not true immobility – at least the regularity and permanence that Greek philosophers typically associated with the divine. It erased the dynamism preserved in Babylonian arithmetic-based astronomy, where numerical progressions conferred both a temporal and generative structure to astronomical change. In Greek astronomy, the concern shifted from predicting the future to understanding the structure of the cosmos: a quest for what is stable and enduring beneath the shifting phenomena of becoming.

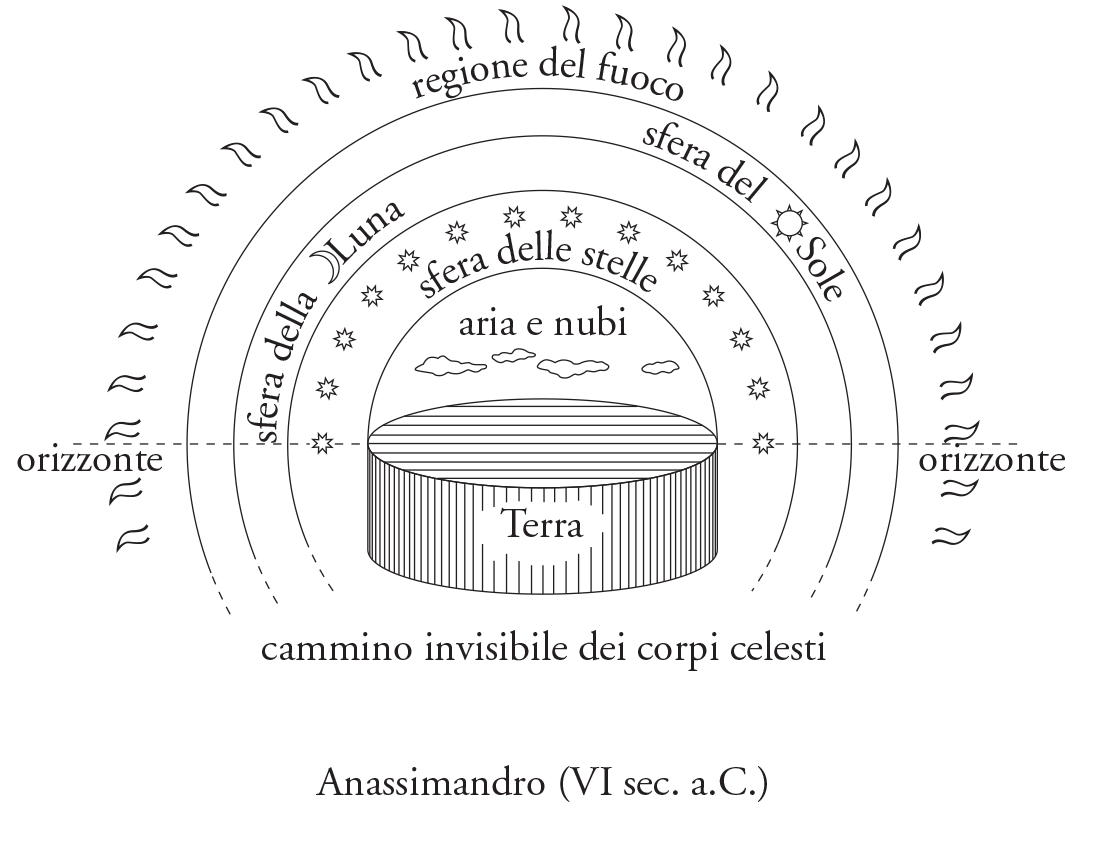

In Ionia, the earliest natural philosophers (physiológoi) proposed various ‘proto-geometrical’ astronomical models. Anaximander, for instance, placed the Earth at the center of the cosmos, maintaining that it remains in equilibrium because it is equidistant from all things (Hippolytus, Philosophoumena, I, 6; Aetius, Placita Philosophorum, II, XX, 1; II, XXI, 1; II, XXV, 1). He envisioned the Earth as a cylinder whose height was one-third its diameter, surrounded by three concentric rings: the ring of the fixed stars (closest to the Earth), followed by that of the Moon, and finally that of the Sun. The diameters of these rings were respectively 9, 18, and 27 times the diameter of the Earth. Regardless of the accuracy of these details – as reported by later doxographers – the model is unmistakably geometric. Arithmetic appears only in the use of the number 3, in a form more suggestive of proportions than of progressions. It plays no role in predicting stellar positions, but rather in articulating the structure of the cosmos.

Despite this early ‘proto-geometrization,’ the Ionian physiológoi maintained a rather concrete conception of the world (with Anaximander likely being the most abstract among them). Astronomical phenomena were still more or less conflated with meteorological processes, and explanations for both were based on physical analogies drawn from everyday experience – such as the fire we feed or the sustaining force of air. It was the Pythagoreans who are generally credited with the true invention of geometric astronomy.

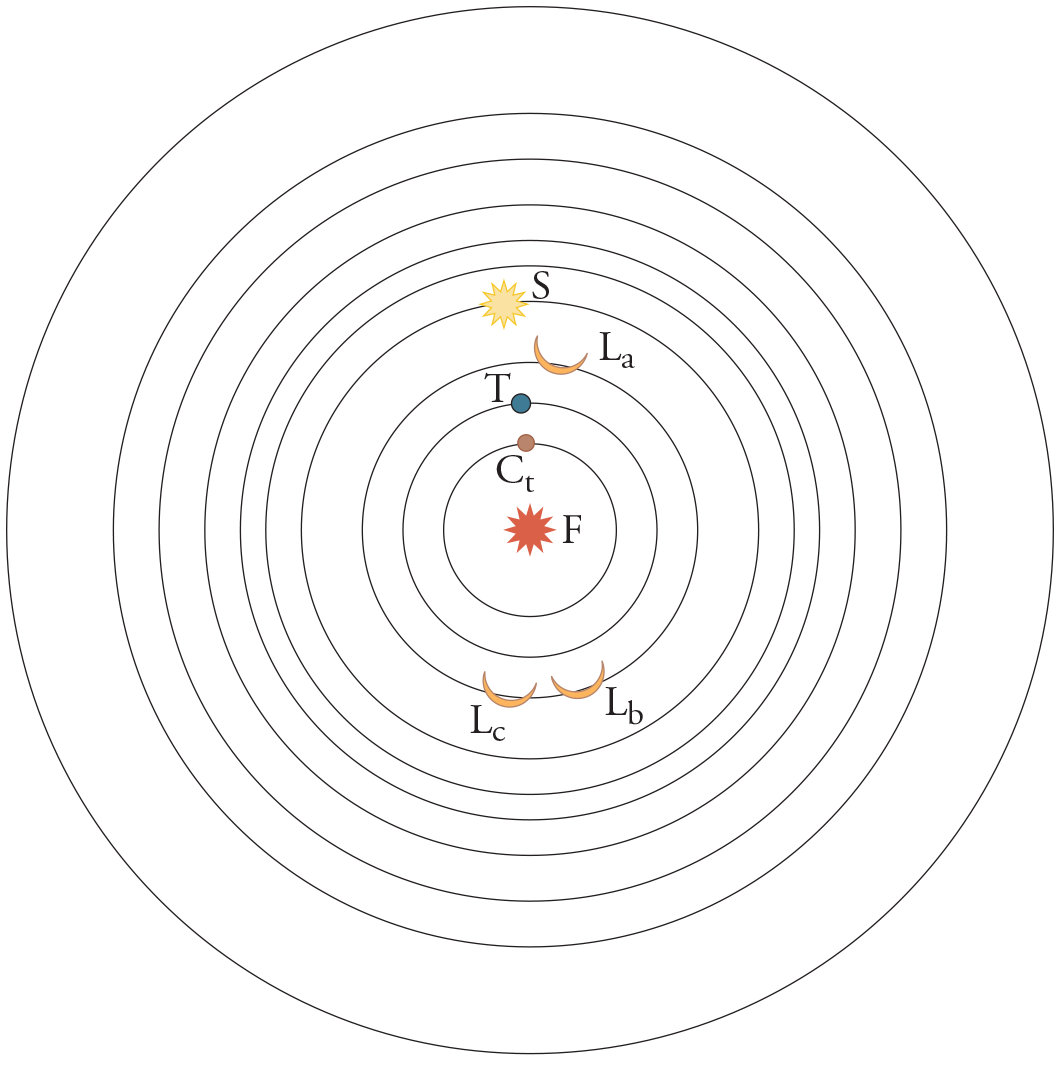

Their most renowned astronomical model – that of Philolaus – was notably non-geocentric. At the center of the universe, Philolaus placed a central fire, the seat of a divinity that governed the motions of the heavens. Around this fire revolved ten celestial bodies (or groups): the Anti-Earth, the Earth, the Moon, the Sun, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, and the fixed stars (Aetius, Placita, II, VII, 7). To reach the sacred number 10, so significant in Pythagorean doctrine, Philolaus had to postulate an imaginary celestial body – the Anti-Earth. According to Plutarch (De animae procreatione in Timaeo, XXXI), the radii of these orbits were as follows: taking the diameter of the central fire as 1, that of the Anti-Earth’s orbit was 3, the Earth’s was 9 (\(5^3\)), the Moon’s 27 (\(5^3\)), Mercury’s 81 (\(5^4\)), Venus’s 243 (\(5^5\)), and the Sun’s 729 (\(5^6\)), with similar progressions for the outer planets. Once again, we find the number 3, which had already played a symbolic role in Anaximander's model. While the ordering of celestial bodies differs among ancient sources, the specific arrangement is secondary. What matters most is the geometric character of this cosmology – a structured, intelligible vision of the universe, rather than a system for predicting future positions using arithmetic progressions.

Arithmetic does still play a role: in the ratios between the orbital diameters, and more symbolically, in the inclusion of the Anti-Earth to complete a numerically harmonious system. Arithmetic is also apparent in the connection drawn between astronomy and music. The Pythagoreans had mathematized music using ratios, and this became the branch of their ‘physics’ where arithmetic found its most concrete application. Music thus served as the paradigm for the “governance of the world through numbers,” particularly in astronomy.

The harmony of the spheres was not only a metaphor for cosmic order – it was also taken quite literally as celestial music. The moving celestial bodies, especially the stars, were thought to produce sounds: the faster their motion, the higher the pitch. Based on the ratios between their orbital diameters and velocities, the stars were believed to generate a harmonious sound. Ancient doxographical accounts differ in how they describe this cosmic harmony, and it remains uncertain how the Pythagoreans themselves understood it. Nonetheless, it seems that the dynamic dimension of astronomy (movement) was linked to arithmetic through music, while geometry pertained to the static depiction of orbits – what was ‘fixed’ in the midst of motion.

Broadly speaking, the comparison between Babylonian and Greek astronomy shows that in Greece – even before the discovery of irrational numbers – geometry increasingly took precedence over arithmetic in the mathematical investigation of nature. At the same time, proportion replaced progression. Progression concerns the generation of an n-th term from the preceding ones; proportion, by contrast, focuses on the relationships between terms – on structure. The Greek focus was on intelligibility over prediction, on ‘pure’ knowledge over practical utility. Even when Greece appropriated some of Babylon’s ‘positive’ astronomical knowledge, it reinterpreted it within a wholly different conceptual framework (excluding here the later developments of Hellenistic astrology).

Medicine presents a different problem. First of all, it is not a science but an art: the effectiveness of treatments takes precedence over the explanation of diseases and their cures. In antiquity, such explanations were often vague, rooted initially in mysticism and magic. They either served as simple a posteriori justifications for empirically discovered remedies or supported practices like incantations, exorcisms, and other forms of magical healing. When these explanations were no longer satisfactory, the aim was not to replace them with rational demonstrations, but rather to frame them within a naturalistic context – typically using analogies – to account for health, disease, and the effects of treatments. This shift did eliminate certain magical elements, but it did not yield genuine therapeutic progress.

The naturalistic interpretation of disease began to emerge well before Hippocrates (c. 460–360 BCE). Traces of it can be found in Mesopotamian sources, and more clearly in Egyptian texts. In Mesopotamia, the Akkadian treatise on medical diagnoses and prognoses (7th century BCE, possibly based on earlier documents; see Labat 1951) already distinguishes between texts devoted strictly to magic and exorcism and those with a more medical appearance. While many of the latter still invoke supernatural causes – divine punishment, curses, or the ‘hand of a specter’ – they also acknowledge natural causes such as ‘dust attack’ or ‘drought fever.’ These texts reflect the beginnings of a systematic approach to symptom assessment and the establishment of prognoses (e.g., whether a cure is possible or not), and even a rudimentary form of diagnosis. As for treatments, while incantations and concoctions worthy of fairy-tale witches are frequent, one also finds natural remedies comparable to those of Egypt or the Hippocratic corpus.

In Egypt, the most extensive surviving medical text, the Ebers Papyrus (1550 BCE), opens with a few incantations intended to enhance the effectiveness of remedies, but thereafter includes only natural treatments. Ailments are classified according to the parts of the body affected. As with Mesopotamian medicine, the effectiveness of these remedies is difficult to determine. Some bear traces of magical origins – though far less so than in Mesopotamia – while others appear to be empirical recipes.

The most remarkable achievement in this domain is the Smith Papyrus (c. 1650 BCE), whose recto is entirely devoted to surgery. Its structure is significantly more systematic than that of the Ebers Papyrus. Ailments are organized by the affected body part, and each case follows a consistent format: name of the ailment, examination of the patient, diagnosis, prognosis (in three possible forms: ‘an ailment I will treat,’ ‘an ailment I will fight,’ or ‘an ailment I will not treat’), treatment, and commentary. These treatments must have had some degree of effectiveness, if only because they avoided harmful interventions.

Egyptian surgery thus appears to have progressed further than medicine along the path of naturalization and rationalization. This is likely due to the mechanical nature of surgical procedures – such as setting fractures or dislocations – which facilitates understanding. In contrast, the mechanisms of action of medicinal drugs remained obscure. More generally, human actions involving mechanical processes (e.g., wheels, pulleys, levers, spinning, weaving, architecture, or surgery) tend to elude magical interpretations more easily than non-mechanical actions, which continued to populate the vast realm of alchemy. This applies to early pottery and metallurgy (where fire’s effects on clay or metal were seen as magical), chemical techniques (e.g., dye-making, glass production), and medicinal pharmacology. Ancient medicine and surgery could rely only on empiricism to achieve some measure of efficacy. Yet in the case of surgery, that empiricism was reinforced by a kind of intelligibility that medicine lacked – hence the early development of a surgical practice more effective than medical treatment.

The Smith Papyrus, like the Ebers, is clearly the result of long-standing practice and careful observation, systematically recorded. Ancient authors frequently extol Egyptian medical expertise. Herodotus (Histories, II, 84) notes that physicians were specialists: some treated eye diseases, others abdominal conditions, and so on. Strabo (Geography, XVII) reports that the Egyptians documented illnesses and remedies in temple registers. Diodorus (Library of History, I, 82) adds that doctors were required to follow the prescriptions set forth in these records. All this supports the existence of a strong medical empiricism in ancient Egypt.

A comparable development can be observed in Greek medicine, which was originally associated with temples. Strabo (Geography, XIV) claims that Hippocrates studied “the records of treatments that were deposited in the temple of Cos.” However, the Hippocratic corpus goes beyond mere empiricism by defining health and disease within the framework of the theory of humours. This theory outlines a physiology in which the body is composed of four humours: blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. Health results from the balance, correct proportion, and proper mixture of these humours; disease arises from their imbalance. This physiology thus grants disease a kind of ‘naturalness’ that goes beyond merely identifying a natural cause (such as climate or diet); it places illness within a systematic framework. Despite the simplistic and inaccurate nature of this theory, which had limited therapeutic consequences, it changed the spirit of medicine. Its explanatory model resembled the kind of physics that had been developed in Ionia shortly before Hippocrates.

In contrast to the Pythagorean mathematical tendencies cultivated in Magna Graecia, the Ionian thinkers attempted to construct a physics in which a single element (water for Thales, air for Anaximenes) served as the origin and substance of all things – that is, a ‘naturalization’ of explanation. This naturalization might still borrow a little from myth (e.g., the Ocean for Thales), but it primarily relied on analogies with everyday experience: water evaporates and thus becomes air; it leaves behind mineral deposits during evaporation, and thus becomes stone. While not yet a science, this effort ‘secularized’ explanation, gradually distancing it from magical thinking. The conception of health as balance (or proportion) comes from Pythagoreanism (it is attributed to Alcmaeon), but the ‘naturalness’ introduced by the theory of humours clearly derives from Ionian physics.

Nothing comparable is known from Egypt, and even less so from Babylonia. However, the Ebers Papyrus contains the beginnings of an attempt to explain disease within a physiological framework – an approach that recalls certain aspects later found in the Hippocratic corpus.

For instance, the papyrus explains syncope as resulting from the heart “no longer speaking,” and fainting as being caused by vessels carrying waste. In the Hippocratic treatise On the Sacred Disease, epilepsy is said to occur in phlegmatic individuals because phlegm can obstruct the vessels that carry air, especially to the brain – leading to loss of consciousness, since in this treatise air (traditionally life-giving) is supposed to produce thought in the brain.

It is hard not to see a parallel between the Egyptian and Hippocratic explanations, although it is impossible to determine whether this reflects direct borrowing or mere convergence. This, however, is not the essential point. What matters is that Egypt appears to have made an early attempt to explain disease in physiological terms – even if that physiology was rudimentary and seemingly not integrated with a physics comparable to that of the Ionians.

At its beginnings, Greek science was marked by a dual current. On the one hand, there was the naturalization of explanation, evident in Ionian physics and Hippocratic medicine – a naturalization whose primary mode was analogy. On the other hand, there was Pythagorean or Pythagorean-inspired mathematism, which encompassed the pursuit of demonstrations in mathematics, their organization into a coherent corpus (culminating in Euclid’s Elements), and the attempt to apply mathematical reasoning to the natural sciences – that is, an explanation grounded in mathematical intelligibility rather than analogy. While the naturalization of explanation may have had some precedents in Mesopotamia and Egypt – particularly in medicine – mathematical intelligibility appears to be a uniquely Greek innovation. Mesopotamian and Egyptian mathematics, and Babylonian astronomy, were more concerned with procedures than with conceptual understanding.

Paradoxically, the Ionian model of naturalization left unresolved the very question of nature and its forces. It explained phenomena inaccessible to human perception by reducing them, through analogy, to physical processes within human reach (e.g., the light of the stars was likened to combustion). But these familiar physical processes were not themselves the object of inquiry; they simply served as analogical supports. To say that the Sun is an incandescent stone ‘naturalizes’ it by comparing it to a heated rock, but this neither explains the Sun nor the nature of stone and fire. This form of naturalization demystifies the world more than it truly explains it. It opens the door to scientific explanation by removing myth as the primary explanatory framework – but it can also close off inquiry when the analogy is accepted as sufficient. Thus, Ionian physics and Hippocratic medicine, however admirable, ultimately proved to be intellectual dead ends. This suggests that for both Greek science and our own, this current is less foundational and less fruitful than the one that prioritizes mathematical intelligibility. It is therefore on this latter tradition that we will primarily focus.

To explain the transition from ‘barbarian’ sciences to Greek science, scholars often point to three events that occurred around the same period in the Greek world, or at its margins. The first is the invention of the alphabet, whereas earlier scripts were consonantal, syllabic, or more commonly mixed (both ideographic and phonetic). The second is the invention of coinage, in Lydia during the reign of Croesus. The third – and likely the most significant – is the birth of democracy. Each of these events has its own distinct causes, more or less identifiable, but they are all linked insofar as they express a shared movement of thought. While we will touch on this general trend, our primary interest will be in democracy, as it is the most consequential of the three.

Philosophy and science are often said to be linked to the democratic habit of subjecting all things to the critical discourse of citizens. This is plausible, but requires further clarification: the Mesopotamians and Egyptians likely engaged in discussion just as the Greeks did – but these discussions had very different implications. The essential difference lies in the nature of political participation. In Greek democracy, civic life was conceived through laws that men gave to themselves, whereas in the Egyptian and Mesopotamian empires, it was experienced as submission to supposedly divine laws.

In Egypt, the pharaoh was deified, and the clergy played an active political role. Mesopotamia was less theocratic, especially in its later stages, but divine legitimacy remained central. The oldest known code – the Code of Hammurabi – concludes with the statement: “Hammurabi, king of justice, I am he to whom Shamash has given the laws” (column XXV, 95-98). Shamash being the sun god, these laws are of divine origin. In archaic Greece, kings were also believed to hold power from the gods and had religious functions. But in the democratic city-states of classical Greece, this connection was severed.

Egypt and Mesopotamia knew law and even written laws. What Greece introduced, however – and this is crucial – was the principle of the political constitution. (See, for instance, Aristotle’s Constitution of Athens for the city’s political history.) Whereas in Egypt and Mesopotamia power operated through laws but was not governed by them (except by the gods who supposedly issued them), in Greece, power was constrained by constitutional laws and could operate only by adhering to them. Citizens’ relationships with political authority were thus mediated through laws, and were apprehended rationally. In contrast, in Egypt and Mesopotamia, subjects’ relations to their rulers were based on raw power, experienced rather than reasoned, and legitimized by myth affirming the ruler’s divinity. The same applies to interpersonal relations. In ancient empires, these relations were structured by a social hierarchy (castes, classes, etc.) sustained by myth; in Greece, they were mediated by constitutional laws or economic conditions, which these laws could reflect.

In the ancient empires, the political and social order, while originating from the divine, was not distinct from the order of nature – both were under the domain of the gods. There was, if not continuity, at least a deep interrelation between nature, society, and the divine. In a democracy, by contrast, the political and social order is a human order. By freeing itself from divine authority, it also distances itself from nature. Thus, politics and society become autonomous realms, distinct from both nature and the divine. This autonomy demands its own principles and structure. It is here that the citizens’ critical discourse – and thus language – comes into play.

Through language, humans attempt to express their experience of themselves and the world, whether for communication or personal reflection. The earliest forms of language likely bore little resemblance to the structured systems analyzed by modern linguists – with signifiers, signifieds, and syntax. Their value lay in expressive capacity – an expressiveness closer to that of poetry (as old as language itself), or to myth, whose power lies more in evocation and analogy than in rational explanation.

This early language stands to modern linguistic language as ideographic writing stands to alphabetic writing. Babylonian or Egyptian ideographic scripts adhered closely to the reality they sought to express. Their expressiveness was raw, immediate, and ungrammatical. Alphabetic writing, by contrast, is mediated: it relies on convention and demands stricter grammar. In ideographic writing and early language, what is to be expressed dominates how it is expressed – the sign is subordinate to the meaning, and the meaning exceeds the sign. In alphabetic writing and evolved language, the sign prevails; what is to be expressed must conform, as best as possible, to the codified structure of expression.

This early form of language did not (or only barely) separate man from the world. Grammar had not yet inserted itself between them, as it does when humans apprehend the world through a system of ‘signifieds’ articulated according to the syntax that governs ‘signifiers.’ Far from being bound by mere convention, the word and the thing shared an intimate connection, one that intertwined them – and this intimacy took precedence over grammatical formalism. Early language thus maintained a strong adhesion to the reality it aimed to express. At the same time, however, it distinguished itself from that reality and exercised a kind of magical power over it – the same power found in incantations, blessings, and curses; the same belief that knowing the name of a person or a thing grants power over it. This magical power of the word can also be found in the ancient belief in the creative force of the divine word – a belief widespread in Mesopotamia, the Near East, and Egypt. For this kind of language, there exists a problem of ontological level akin to that of numbers: the word does not have the same level of existence as the thing it designates, yet it remains closely enough linked to exert power over it (with the difference that a word must usually be spoken to have effect, whereas a number’s power is more ‘structural’).

Gradually, this magical aspect receded, and language began to resemble what we know today: a system that imposes its form on representations of the world but, through its standardization, facilitates communication. Grammatical expression developed at the expense of the raw expressiveness found in poetry and myth; grammar inserted its ‘reading grid’ between humans and the world. Language’s expressive power thus increasingly passed through the mold of grammar, which came to shape human experience of the world. Experience, then, tended to be ‘grammatically’ conceived rather than directly lived (as poetry and myth had formerly expressed).

Language thereby gained autonomy from what it sought to express; it adhered to reality less and less. By interposing itself between humans and the world, it no longer fully belonged to either. Separated from the world, it lost its magical potency: the connection between word and thing became merely conventional; incantations, blessings, and curses faded. Separated from man, language began to function independently. It no longer subordinated itself to lived experience, but forced that experience into the framework of grammar. At the same time, it became ‘bulimic,’ sifting through and categorizing everything.

This autonomy of language can be compared to that of money, the third invention commonly associated with the emergence of philosophy and science. Money, too, stands between man and the world. Where once there had been an immediate grasp of objects – their utility and symbolic value (through consumption or barter) – money introduced a dual system: that of commodity, with both use value and exchange value (Baudrillard 1972). A system that tends toward autonomy, functioning for and by itself.

Yet it is especially language and the political system that must be compared. The raw, ungrammatical expressiveness of early language parallels the way that participation in ancient empires was experienced immediately – not reasoned through a constitution (a kind of ‘political grammar’ that interposes a social order between man and the world). In contrast, the ‘grammatical’ language must be associated with democracy. Here, the parallel becomes a convergence: in a democracy, the need for individuals to reason about their position within an autonomous political order may have encouraged them to perceive the world as a cosmos – an ordered whole – and to conceive their place in it through discourse, privileging intelligibility over the raw expressiveness of poetry and myth. This linguistic evolution had likely begun much earlier, but democracy institutionalized it by making rational discourse an ideal. The autonomy of language, the dominance of grammar, and the decline of its magical adherence to reality are thus deeply linked to the democratic system.

In a democracy, the only remaining power of language is persuasion through speech. This is what Gorgias says in the Encomium of Helen (DK 82 B 11). But persuasion is not truth, and when language lacks grounding in adherence to reality, it risks becoming sophistry – a form of linguistic intoxication that claims to prove anything. The autonomy of language is not enough; it must be structured and principled – just as the political field must be. Sophistry finds its political counterpart in demagogy. Plato and Aristotle attempted to respond to this challenge: the one with his dialectic, the other with his logic. These were efforts to impose proper order on discursive thought, born from the rise of an autonomous ‘grammatical’ language, at the expense of the language of poetry and myth. But where does this drive for rationalization come from?

The turbulent political life of the Greek city-states and the tendency to subject everything to the critical discourse of citizens undoubtedly contributed to introducing order into thought – whether political, philosophical, or scientific. The excesses of sophistry eventually turned against it, thus delineating its limits of validity. Yet another factor may have played a decisive role: mathematics as a model of true knowledge.

The pursuit of intelligibility, inherent to democratic discourse, could only support the rise of mathematics. Mathematics benefited from the broader cultural movement by which language broke free from its magical adhesions to reality, becoming more grammatical and autonomous. However, mathematics, once initiated, did not import its rigor from outside; it discovered it within itself. It made numbers and figures its proper objects by considering them in and of themselves – as elements of an autonomous world with its own intrinsic properties – and it developed appropriate methods to engage with them.

The nature of these mathematical objects remains poorly defined. Their ontological status – Plato famously positioned them between the sensible world and the world of Forms – is as difficult to specify as that of language itself. Yet they constitute a far more coherent, rigorous, and unified structure than anything grammar can offer to language. One need only recall the earlier example of the sum of successive odd numbers: the arithmetic property reveals itself almost effortlessly, just as the geometry of square duplication becomes clear to the slave in Plato’s Meno (82a-86b). This unified and rigorous structure would come to serve as a model for knowledge – one that Plato even sought to surpass through his dialectic, which relegates mathematics to a merely preparatory role. A kind of reciprocal influence developed between philosophy and mathematics: philosophers – especially Plato – helped clarify the mathematical approach, while also drawing upon it as a model to construct equally rigorous forms of thought, applied to broader domains (politics, ethics, the natural sciences).

Mesopotamia and Egypt accumulated considerable factual knowledge – mathematics, astronomy, and medicine – either for practical purposes (agriculture, commerce, calendar-making, etc.) or within a mystical framework (astrology, the magic of words and numbers). But in neither case was intelligibility ever established as a criterion of truth.

In Greece, by contrast, democracy fostered the autonomy of language, the severing of its magical ties to reality, and the rise of grammar – thus promoting a form of discursive thought that privileges intelligibility, even though it sometimes degenerated into sophistry, where persuasion took precedence over truth. In parallel, democracy also supported the development of a particular kind of ‘discursivity’: mathematical reasoning. Like language, its domain was autonomous – but its construction was far superior. This gave mathematics a rigor and intelligibility far beyond that of rhetorical techniques based on persuasion. Mathematics thus became a model, informing both Platonic dialectic and Aristotelian logic – tools intended to discipline the autonomy of ‘grammatical’ language when misused by sophistry. From this convergence emerged both philosophy and Greek science.

Greek science undoubtedly borrowed factual knowledge from Mesopotamia and Egypt, but it reformulated it in a distinctive intellectual spirit. It was not so much these borrowings – valuable though they were – as this spirit that guaranteed its development and lasting influence.

André Pichot

References

- Baudrillard 1972: Baudrillard, Jean, Pour une critique de l’économie politique du signe, Paris, Gallimard, 1972.

- Bottéro 1952: Bottéro, Jean, La religion babylonienne, Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, 1952.

- Burnet 1892: Burnet, John, Early Greek Philosophy, London, A. & C. Black, 1892 (4th ed.: 1952).

- Caveing 1994-97: Caveing, Maurice, La constitution du type mathématique de l’idéalité dans la pensée grecque, Lille, Presses Universitaires de Lille, 1994–1997, 2 vols.

- Chace 1927-29:, Chace A.B. et al., The Rhind Mathematical Papyrus, Oberlin (Ohio), Mathematical Association of America, 1927–1929, 2 vols.

- Contenau 1938: Contenau, Georges, La médecine en Assyrie et en Babylonie, Paris, Maloine, 1938.

- – 1940: Contenau, Georges, La divination chez les Assyriens et les Babyloniens, Paris, Payot, 1940.

- Duhem 1913-29: Duhem, Pierre M.M., Le système du monde. Histoire des doctrines cosmologiques de Platon à Copernic, Paris, A. Hermann, 1913–1959, 10 vols.; vol. I, 1954.

- Dumont 1988: Dumont, Jean-Paul (ed.), Les Présocratiques, Paris, Gallimard, 1988.

- Ellul 1961: Ellul, Jacques, Histoire des institutions de l’Antiquité, nouvelle éd., Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, 1961.

- Février 1959: Février, James Germain, Histoire de l’écriture, nouv. éd. entièrement refondue, Paris, Payot, 1959 (1st ed.: 1948).

- Finley 1970: Finley, Moses I., Early Greece. The Bronze and Archaic Ages, London, Chatto & Windus, 1970.

- Gaudemet 1967: Gaudemet, Jean, Institutions de l’Antiquité, Paris, Sirey, 1967.

- Goody 1977: Goody, Jack, The Domestication of the Savage Mind, Cambridge–New York, Cambridge University Press, 1977.

- – 1986: Goody, Jack, Logic of Writing and the Organization of Society, Cambridge–New York, Cambridge University Press, 1986.

- Guitel 1975: Guitel, Geneviève, Histoire comparée des numérations écrites, Paris, Flammarion, 1975.

- Heath 1949: Heath, Thomas L., Mathematics in Aristotle, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1949 (repr. New York, Garland Publ., 1980).

- Ifrah 1994: Ifrah, Georges, Histoire universelle des chiffres, Paris, R. Laffont, 1994.

- Kramer 1956: Kramer, Samuel Noah, From the Tablets of Sumer, Indian Hills (Col.), Falcon’s Wing Press, 1956.

- Labat 1951: Labat, René (ed.), Traité akkadien des diagnostics et pronostics médicaux, Paris, Académie internationale d’histoire des sciences, 1951, 2 vols.

- Lloyd 1970: Lloyd, Geoffrey E.R., Early Greek Science: Thales to Aristotle, London, Chatto & Windus, 1970.

- – 1979: Lloyd, Geoffrey E.R., Magic, Reason, and Experience, Cambridge–New York, Cambridge University Press, 1979.

- Michel 1950: Michel, Paul-Henri, De Pythagore à Euclide, Paris, Les Belles Lettres, 1950.

- Morenz 1960: Morenz, Siegfried, Ägyptische Religion, Stuttgart, Kohlhammer, 1960 (trad. it. La religione egizia, Milano, Il Saggiatore, 1968).

- Neugebauer 1951: Neugebauer, Otto, The Exact Sciences in Antiquity, Copenhagen, E. Munksgaard, 1951 (2nd ed. Providence, Brown University Press, 1957).

- – 1955: Neugebauer, Otto, Astronomical Cuneiform Texts, London, Lund Humphries, 1955, 3 vols.

- Pichot 1991: Pichot, André, La naissance de la science, Paris, Gallimard, 1991, 2 vols. (trad. it. La nascita della scienza, Bari, Dedalo, 1993).

- Rey 1930-48: Rey, Abel, La science dans l’Antiquité, Paris, La Renaissance du Livre, 1930–1948, 5 vols.

- Robin 1973: Robin, Léon, La pensée grecque et les origines de l’esprit scientifique, Paris, A. Michel, 1973.

- Vernant 1962: Vernant, Jean-Pierre, Les origines de la pensée grecque, Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, 1962 (4th ed.: 1981).

- – 1965: Vernant, Jean-Pierre, Mythe et pensée chez les Grecs, Paris, F. Maspero, 1965.